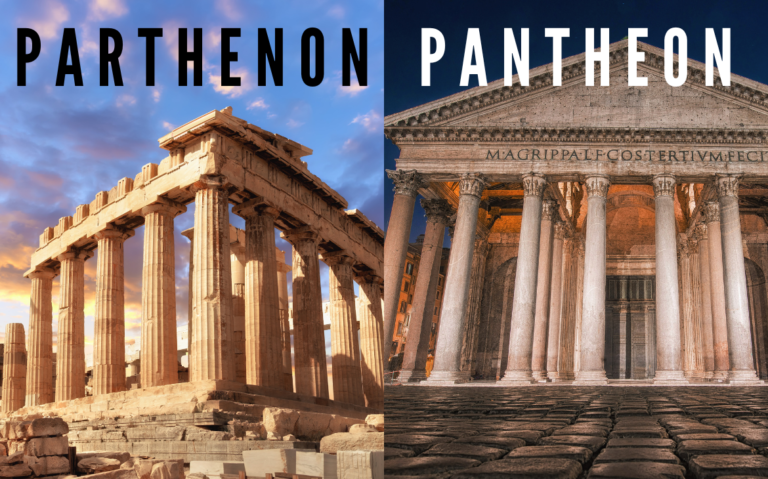

Stand beneath the Pantheon’s massive dome in Rome, and you’ll feel something shift inside you. Maybe it’s the way sunlight streams through that perfect circular opening at the top. Or how the building seems to breathe, alive after nearly 2,000 years. But here’s what really gets me: we still can’t fully explain how the Romans pulled this off.

The pantheon construction represents the peak of ancient Roman engineering. While countless Roman structures have crumbled into ruins, this building stands almost exactly as it did when Emperor Hadrian’s builders finished it around 125 AD. Modern engineers study it. Architects make pilgrimages to see it. And tourists who step inside for the first time often just stop and stare upward, mouths open.

What makes this building so special? It holds the world’s largest unreinforced concrete dome. No steel beams. No modern materials. Just Roman concrete, clever design, and construction techniques that we’re still trying to fully understand today. The dome spans 142 feet across, and after 1,900 years, it hasn’t cracked or collapsed. Most concrete structures built in the last century can’t claim that kind of durability.

If you’re planning a trip to Rome or just fascinated by how ancient civilizations built things that outlast our modern construction, you’re in the right place. This guide walks you through everything that makes the pantheon construction so remarkable. You’ll discover the secrets behind that incredible dome, learn about the materials that have lasted for millennia, and find out how to experience this architectural wonder in person.

Let’s dig into why this building changed architecture forever.

The Pantheon: What You Need to Know Before You Visit

The Pantheon sits in the heart of Rome’s historic center, right on the Piazza della Rotonda. You can’t miss it. The building dominates the square, and there’s usually a crowd gathered outside, craning their necks to take it all in.

Emperor Hadrian commissioned this version of the Pantheon between 113 and 125 AD. Yes, I said “this version” because an earlier temple burned down. But Hadrian’s building? It’s survived everything history threw at it. Wars, earthquakes, floods, looters who stripped away bronze and marble. Through it all, the core structure remained solid.

Here’s something that surprises most visitors: entry is free. You can walk right in and experience one of humanity’s greatest architectural achievements without paying a cent. The building now serves as a church, officially called Santa Maria ad Martyres, which is actually part of why it’s so well preserved. When the Byzantine Emperor gave it to the Pope in 609 AD, it gained protection that saved it from being quarried for building materials like so many other Roman structures.

The Pantheon earned UNESCO World Heritage status as part of the Historic Centre of Rome. But unlike many heritage sites that feel like museums, this place still functions. People worship here. Couples get married under that dome. The building lives and breathes as more than just a monument to the past.

The best part? The location puts you right in the middle of Rome’s most charming neighborhood. After you visit, you’re a short walk from the Trevi Fountain, Piazza Navona, and dozens of cafes where you can sit with an espresso and process what you just experienced.

Most people spend about 30 minutes inside, but I’d recommend giving yourself at least an hour. You’ll want time to really look at the construction details, watch how the light changes through the oculus, and just soak in the space.

The Revolutionary Concrete Dome That Changed Everything

Let’s talk about what makes the pantheon construction truly mind blowing. That dome isn’t just big. It’s a masterpiece of engineering that shouldn’t even be possible with ancient technology.

The dome measures 43.3 meters (about 142 feet) in diameter. For almost 1,800 years, no one built a larger unreinforced concrete dome. Think about that. The Renaissance came and went. The Industrial Revolution happened. We invented steel and modern concrete. And still, nobody matched what Roman builders achieved in 125 AD until the 20th century.

The secret lies in Roman concrete, or what they called opus caementicium. This wasn’t like the concrete we use today. The Romans mixed volcanic ash from Pozzuoli (near Naples) with lime and water, creating a material that actually gets stronger over time, especially when exposed to seawater. Modern concrete starts degrading after a few decades. Roman concrete from the pantheon construction is still going strong after two millennia.

But here’s where it gets really clever. The builders didn’t use the same concrete mix throughout the entire dome. At the base, where the dome needs to support the most weight, they used heavy aggregate like travertine and brick. As they built upward, they gradually switched to lighter materials. Near the top, they used pumice, a volcanic rock so light it can float in water.

This progressive lightening technique reduced the dome’s overall weight without sacrificing strength. The transition happens so gradually that you can’t see where one type of concrete ends and another begins. The builders understood something about stress distribution that wouldn’t be formally written down in engineering textbooks for another 1,500 years.

The dome’s thickness also decreases as it rises. At the base, the concrete is about 21 feet thick. At the top, near the oculus, it’s only about 4 feet thick. Less weight up high means less stress on the entire structure.

Look closely at the dome’s interior and you’ll see those famous coffered squares, arranged in five rings. Most people think they’re purely decorative. They’re beautiful, sure, but they also serve a structural purpose. Each coffer reduces weight while the ribs between them provide strength. Form and function working together perfectly.

The dome rests on a massive cylindrical rotunda with walls 20 feet thick. These walls aren’t solid concrete either. Hidden inside are brick relieving arches that channel the dome’s outward thrust downward into the foundation. You can’t see these arches from inside or outside the building, but they’re doing the heavy lifting, literally.

Modern architects and engineers still study the pantheon construction techniques. Recent research using advanced imaging technology revealed that the dome has tiny cracks, but they’re stable. The building has found its equilibrium. It’s settled into a state where all the forces balance each other out.

Some researchers think the Romans used temporary wooden formwork to support the dome during construction, then removed it once the concrete cured. Others believe they might have built it in horizontal layers, letting each layer set before adding the next. We don’t have the construction plans, so we’re left piecing together the method from the building itself.

What we do know for certain is this: the pantheon construction represents a level of engineering sophistication that took humanity over a thousand years to reach again.

The Oculus: A Hole That Makes Perfect Sense

The most dramatic feature of the Pantheon is that massive opening at the top of the dome. The oculus measures about 30 feet across, and yes, it’s completely open to the sky. No glass. No covering. When it rains in Rome, it rains inside the Pantheon.

Your first thought might be: didn’t the builders know how to close it? Of course they did. The oculus is intentional, and it’s brilliant for multiple reasons.

First, it solves a huge structural problem. The top of a dome experiences the most stress from all the weight trying to push outward. By leaving it open, the builders eliminated weight at the most critical point. The oculus essentially acts like a compression ring, with all the forces of the dome directed around it.

Second, it brings in light. The Pantheon has no windows. All the natural light comes through that single opening at the top. As the sun moves across the sky, a beam of light sweeps around the interior like the hand of a cosmic clock. Ancient Romans would have seen this as deeply symbolic, a connection between the earthly temple and the heavens.

The lighting effect is stunning. If you visit at different times of day, you’ll see completely different buildings. Morning light creates sharp shadows that highlight the coffers. Afternoon sun bathes the marble floor in warm gold. On rainy days, the diffused light turns everything soft and ethereal.

Third, the oculus provides ventilation. Air flows up through the opening, creating natural circulation that keeps the interior comfortable even in Rome’s hot summers. No air conditioning needed.

But what about the rain? Here’s where the Roman engineers really showed off. The marble floor has a slight slope toward the center, where a series of drainage holes channels water away. The system works so well that even during heavy storms, you’ll only see small puddles on the floor. The water drains faster than it falls.

The oculus also affects how you experience the space. That opening draws your eye upward. It creates a sense of openness and connection to the sky that makes the building feel larger than it actually is. You’re standing inside and outside at the same time.

Some scholars believe the oculus had religious significance too. The Pantheon was a temple to all the gods (that’s what “Pantheon” means). The opening to the sky might have represented the connection between worshippers and the divine realm.

Modern buildings sometimes try to recreate this effect with skylights and atriums, but they never quite capture the same feeling. There’s something about knowing you’re looking at the actual sky through a 2,000 year old opening that no modern interpretation can match.

The Materials That Refused to Die

One of the biggest mysteries of pantheon construction is how the materials have lasted so long. While other Roman buildings turned to rubble centuries ago, the Pantheon stands strong. The secret is in what they used and how they used it.

The volcanic ash I mentioned earlier, called pozzolana, comes from deposits near Naples. When mixed with lime and seawater, it creates a chemical reaction that forms crystals. These crystals actually grow over time, filling in cracks and making the concrete stronger as it ages. Scientists studying samples of Roman concrete found that it continues to mineralize and self heal even after 2,000 years.

Modern concrete works differently. It’s strong initially but starts breaking down from day one. Water seeps in, steel reinforcement bars rust and expand, causing more cracks. Within decades, many modern concrete structures need major repairs. The Romans had no steel reinforcement, which turns out to be an advantage. No steel means no rust, no expansion, no accelerated cracking.

The builders used different materials for different parts of the structure. The foundation sits on a bed of concrete mixed with chunks of travertine, a cream colored limestone quarried near Tivoli, just outside Rome. This heavy, dense foundation has kept the building stable through countless earthquakes.

The rotunda walls combine travertine, tufa (another volcanic stone), and brick. The mixture creates walls that are strong enough to support the dome but with just enough flexibility to move slightly during earthquakes without cracking. Rigidity would have been a death sentence. The pantheon construction achieves the perfect balance between strength and flexibility.

The bronze originally played a bigger role in the building. The massive doors you see today are the originals, still hanging on their ancient hinges after 1,900 years. They weigh 20 tons but swing open smoothly. That’s precision craftsmanship.

The dome’s exterior once had bronze tiles covering it. The ceiling of the porch featured bronze beams. Most of that bronze got stripped away over the centuries, melted down for weapons or other buildings. In 1632, Pope Urban VIII took bronze from the Pantheon to make cannons and decorations for St. Peter’s Basilica. Romans at the time had a saying: “What the barbarians didn’t do, the Barberini did.” (Barberini was the Pope’s family name.)

Inside, you’ll see marble everywhere. The columns in the portico are single pieces of Egyptian granite, each weighing about 60 tons. Imagine shipping those from Egypt to Rome, then lifting them into place without modern machinery. The floor features gorgeous patterns of colored marble from across the empire: yellow from North Africa, purple from Turkey, red from Egypt.

The marble floor you walk on today is mostly original, though it’s been repaired over the centuries. The patterns create geometric designs that guide your eye toward the center, directly under the oculus. Everything in the pantheon construction directs your attention and movement.

What’s remarkable is that the Romans sourced materials from across their empire specifically for their properties. They didn’t just use whatever was nearby. They understood that Egyptian granite was better for columns, that volcanic ash from Pozzuoli made superior concrete, that pumice from the slopes of Vesuvius would lighten the dome’s upper reaches. The Pantheon is a material archive of the Roman Empire at its peak.

How They Actually Built It

We don’t have construction documents or ancient Roman building plans for the Pantheon. What we know about how they built it comes from studying the building itself, comparing it to other Roman structures, and some written accounts from ancient authors.

The builders started with that massive foundation, digging down about 15 feet and pouring a concrete ring about 25 feet thick. This foundation distributes the enormous weight of the dome and walls across a wider area of soil. Without it, the building would have sunk into Rome’s soft ground centuries ago.

Next came the cylindrical rotunda walls. Workers built these up in layers, probably using wooden formwork to shape the concrete as it cured. They embedded those hidden brick relieving arches as they went, creating the internal structure that would channel forces from the dome down to the foundation.

For the dome itself, most experts believe the Romans built a massive wooden framework that supported the concrete until it hardened. This framework would have been an engineering project in its own right, requiring huge amounts of timber and skilled carpentry. Once the concrete cured, workers would have removed the wooden structure and reused the timber elsewhere.

Another theory suggests they might have used a combination of framework and a technique where each ring of the dome could support itself once it hardened, allowing them to build upward in stages. The truth might be somewhere between these approaches, or something we haven’t thought of yet.

The coffers had to be formed as part of the concrete pour. Workers probably placed wooden boxes in the right pattern, poured concrete around them, then removed the boxes once the concrete set. Each coffer required precise positioning. Get one wrong, and the pattern would be off across the entire dome.

The workforce must have been substantial. Between the skilled engineers designing the structure, the craftsmen shaping formwork, the laborers mixing and pouring concrete, and the specialized workers setting marble and bronze, hundreds or possibly thousands of people worked on the pantheon construction.

The timeline stretched over 12 years or more. That’s fast for a building this complex, even by modern standards. It suggests an efficient, well organized construction process and substantial funding. Hadrian spared no expense for his grand temple.

Roman builders used surprisingly simple tools: hammers, chisels, levels, plumb lines, and measuring ropes. They had cranes powered by human workers walking inside giant treadwheels, but nothing like modern construction equipment. What they lacked in technology, they made up for with knowledge, skill, and sheer determination.

The finishing work came last: applying the marble veneer to walls, installing those massive bronze doors, setting the floor patterns, and adding decorative elements. Every surface received attention. The Romans didn’t believe in leaving rough concrete exposed. The structural brilliance was meant to be hidden behind beautiful surfaces.

What impresses me most is the confidence it took to build this. The builders couldn’t run computer simulations. They couldn’t test scale models. They relied on experience, mathematical knowledge passed down through generations, and faith in their understanding of how materials and forces interact. They got it right on the first try. There was no second chance with a dome this large.

Why the Pantheon Stands Alone Among Ancient Structures

Rome has plenty of impressive ancient buildings. The Colosseum draws bigger crowds. The Forum tells more about daily Roman life. But architects and engineers reserve special reverence for the Pantheon, and here’s why.

The Colosseum, as massive and impressive as it is, follows fairly straightforward principles. Stack arches, distribute weight, build thick walls. Romans built countless amphitheaters using similar techniques. The technology was proven and understood.

The pantheon construction broke new ground. Nobody had built a dome this large before. The span exceeded anything attempted previously. If the builders got their calculations wrong, tons of concrete would come crashing down. The risk was enormous, and the achievement unprecedented.

Compare it to the Hagia Sophia in Constantinople, built 400 years after the Pantheon. That building’s dome is impressive, but smaller (about 105 feet across versus 142 feet). And it’s gone through multiple reconstructions after earthquake damage. The original dome partially collapsed just 20 years after construction. The Pantheon’s dome has never fallen.

The Egyptian pyramids represent incredible organizational achievement and astronomical precision, but structurally they’re piles of stone blocks. Gravity holds them together. The pantheon construction required understanding how forces travel through curved surfaces, how materials of different densities interact, and how to create a structure that becomes stronger as the pieces press against each other.

The Pantheon’s influence echoes through architectural history. When Renaissance architect Filippo Brunelleschi needed to design a dome for Florence Cathedral, he studied the Pantheon. The dome he built in the 1400s used similar principles: progressively lighter materials, careful attention to stress distribution, and the courage to attempt something everyone said was impossible.

The US Capitol building features a dome directly inspired by the Pantheon. So does the Panthéon in Paris (even borrowed the name). Thomas Jefferson loved Roman architecture and incorporated Pantheon inspired elements into several buildings, including the Rotunda at the University of Virginia.

What really sets the Pantheon apart is completeness. You’re not looking at ruins and trying to imagine what once stood there. You’re experiencing the building almost exactly as Romans did 1,900 years ago. The proportions, the light, the sense of space, it’s all intact. That’s incredibly rare for ancient architecture.

The building also represents the peak of Roman power and confidence. By Hadrian’s time, the empire stretched from Britain to Mesopotamia, from Germany to North Africa. Resources flowed to Rome from every corner of the known world. The Pantheon showcases that global reach through its materials while demonstrating the engineering knowledge Rome accumulated over centuries of building.

Experience the Pantheon in Person: Your Visit Guide

Reading about the pantheon construction is one thing. Standing inside it is something else entirely. If you’re planning a Rome trip, here’s how to make the most of your visit.

The Pantheon sits at Piazza della Rotonda in central Rome, easy to reach on foot from most tourist areas. The nearest metro station is Barberini on Line A, about a 10 minute walk away. Many people prefer walking through Rome’s historic streets. It’s a beautiful city for exploring on foot, and you’ll stumble across fountains, piazzas, and cafes along the way.

As I mentioned earlier, entry is free. Just walk in during opening hours, which are typically 9 AM to 7 PM on weekdays and 9 AM to 6 PM on Sundays. The building closes on January 1, May 1, and December 25. Since it’s a functioning church, mass is held regularly, and the building may be closed to tourists during services. Check the schedule before you go.

Free entry is great, but it comes with a downside: crowds. The Pantheon draws millions of visitors every year, and it can get packed, especially mid morning to mid afternoon during summer. If you want to experience the space with fewer people, go early morning right when it opens or late afternoon an hour before closing.

Here’s an insider tip: visit on a rainy day. Most tourists skip it when weather is bad, but that’s actually the best time to see the Pantheon. Watching rain pour through the oculus while you stand dry beneath the dome is magical. You’ll also understand how the drainage system works.

Should you book a guided tour? It depends on what you want from the experience. Self guided visits are perfectly fine for taking in the atmosphere and beauty. But if you want to really understand the pantheon construction, a good guide makes a huge difference.

Expert guides point out details you’d miss on your own. They’ll show you the brick relieving arches visible from certain angles, explain how the coffers reduce weight, discuss the marble types and where they came from. They bring the engineering alive in ways that standing and staring can’t quite capture.

Skip the line tours are worth considering during peak season. Even though entry is free, you might wait 30 minutes or more in the regular line. Skip the line tickets (usually around 15 to 25 euros) get you in immediately and often include a guide.

For architecture enthusiasts, specialized architectural tours dig deep into the construction techniques, mathematical proportions, and engineering innovations. These tours typically last 90 minutes to 2 hours and might include access to lesser known viewpoints or detailed discussions with architects or engineers who study Roman construction.

Some tour companies offer combined packages: Pantheon plus other ancient Roman sites like the Forum and Colosseum. These can be efficient if you’re short on time and want expert context for multiple locations.

Virtual tours and audio guide apps exist if you prefer exploring at your own pace with some expert information. Apps like Rick Steves Audio Europe have free Pantheon guides. The quality varies, but they’re better than nothing if you can’t justify the cost of a live guide.

Photography is allowed inside, but be respectful. It’s a church, not just a tourist site. No flash photography, and keep your voice down. The building’s acoustics carry sound, so even quiet conversations echo.

The best photo spots? Stand in the center under the oculus and shoot straight up. You’ll capture that perfect circle of sky framed by coffers. Early morning or late afternoon gives the best light for interior shots. Outside, the portico looks great from the piazza, especially if you can catch it without too many people in the shot.

Don’t rush your visit. I see tourists all the time who dash in, snap a few photos, and leave after 10 minutes. They miss everything. Sit on one of the benches, watch the light move, observe how other visitors react when they first look up. Let the space work its magic on you.

After visiting the Pantheon, the neighborhood is worth exploring. The piazza in front has restaurants (touristy but convenient), and streets radiating away from it are filled with shops, cafes, and gelato spots. The coffee shop Sant’Eustachio is a few minutes’ walk and serves some of Rome’s best espresso.

Piazza Navona is about 5 minutes away on foot. The Trevi Fountain is 10 minutes. You can easily combine the Pantheon with these spots in a single afternoon of walking.

Preserving an Ancient Wonder for Future Generations

The Pantheon has survived this long partly through luck and partly through ongoing care. Today, preserving it requires constant attention.

The Italian Ministry of Cultural Heritage oversees conservation efforts. Teams of specialists monitor the building for any signs of stress, degradation, or damage. Modern technology helps them spot problems before they become serious.

Recent conservation work has included cleaning the marble surfaces, which darken over time from pollution and weathering. Laser cleaning technology can remove dirt without damaging the ancient stone underneath. Workers also maintain the drainage system, making sure those 2,000 year old drain holes keep functioning.

One major challenge is vibration from traffic and foot traffic. Millions of people walking across that marble floor every year creates wear. The street outside carries buses and cars. All that vibration, accumulated over time, can cause stress. Engineers study how vibrations affect the structure and recommend limits on vehicle access when needed.

Climate change brings new concerns. More extreme weather means heavier rainstorms and more stress on the drainage system. Temperature fluctuations can cause building materials to expand and contract, potentially creating cracks. Conservation teams factor these changing conditions into their preservation strategies.

Scientists continue studying Roman concrete, trying to fully understand why it performs so well. Recent research revealed that the concrete contains aluminum tobermorite, a rare mineral that forms through volcanic ash reactions. This discovery might lead to more sustainable modern concrete that lasts longer and produces less carbon dioxide during manufacturing. The ancient Romans might help us solve modern environmental problems.

The Pantheon also benefits from its status as a church. Religious buildings tend to receive better care than abandoned monuments. Regular use means problems get noticed and addressed. The building has purpose beyond being a museum piece.

Tourism provides funding for conservation but also creates challenges. Millions of visitors mean wear and tear. Finding the balance between access and preservation is an ongoing discussion. Should visitor numbers be limited? Should there be an entrance fee to fund conservation? These debates continue.

Final Thought

Walking out of the Pantheon into the bright Rome sunlight always feels a bit like returning from another world. That building does something to you. It makes you think differently about what humans can achieve when they combine knowledge, skill, and ambition.

The pantheon construction happened during a time we often think of as primitive. No computers. No calculators. No steel. No modern understanding of materials science or structural engineering. Yet Roman builders created something that continues to baffle and inspire us two thousand years later.

Every modern concrete structure we build today will likely be rubble long before the Pantheon shows serious signs of decay. Our skyscrapers will fall, our bridges will crumble, our monuments will erode. But that dome over the Piazza della Rotonda? It’ll probably still be there, still drawing people in, still making them look up in wonder.

There’s something humbling about that. We like to think we’re so advanced, that our technology puts us far beyond anything ancient civilizations achieved. Then you stand under that oculus, watching sunlight pour through a hole that’s been open to the sky for 1,900 years, and you realize maybe we’re not as far ahead as we think.

The Pantheon reminds us that great achievements aren’t about having the fanciest tools. They’re about understanding fundamental principles deeply, about patience and precision, about being willing to attempt something everyone says is impossible.

If you ever get the chance to visit Rome, don’t skip the Pantheon. Yes, the Colosseum is impressive. Yes, St. Peter’s is beautiful. But the Pantheon is special in a way that’s hard to put into words. It’s a conversation across centuries, a building that bridges the ancient world and ours.

Stand in that space. Look up through the oculus. Feel the weight of all that concrete hanging above you, held up by Roman engineering genius and nothing else. Let it change your perspective on what’s possible.

The builders who created the pantheon construction are long gone. Their names are forgotten. But their work speaks louder than any monument with a name carved on it. They built something that transcends their time, their empire, even their civilization. They built something that simply is, perfect and complete, requiring no explanation or justification.

That’s the real achievement. Not just engineering excellence, though that’s certainly there. Not just beauty, though the building is undeniably beautiful. The real achievement is creating something so fundamentally right, so perfectly executed, that it just keeps existing, millennium after millennium, outlasting everything and everyone.

Two thousand years from now, will anything we build today still be standing? I don’t know. But I’d bet on the Pantheon.